Article About Charles Washburn Published in Worcester Living

Posted Monday August 10 2009 at 5:31 pm.

Used tags: advocacy, charles_washburn, education, news, vsa

By: Thomas Caywood

As a young arts advocate in Worcester in the 1970s, Charles J. Washburn found himself overcome by a desire to reach out to the most-isolated community he could imagine close at hand: mental patients locked away in the secured wards of Worcester State Hospital.

In what he now concedes was an extravagantly impractical plan, the 20-something activist, not long out of Fairfield University in Connecticut, waded into the state bureaucracy seeking permission from wary hospital administrators to take those patients on a field trip to a rock concert in a city park.

Washburn - who would go on to be one of the founders of First Night Worcester and to run an education nonprofit in Boston - at the time didn't see why he couldn't just find a bus, drive it to the hospital and ferry the mental hospital patients to the concert.

"They thought I was nuts," he recalled recently, grinning at the memory. "I was pretty naive. It turned out they had good reasons to say, 'No.'"

But Washburn didn't give up. The following year he got permission, instead, to bring a folk-rock band to the hospital to perform in one of the locked wards.

That experience helped launch him into what would become his life's work: using the arts to promote education and inclusion of people with disabilities.

"People who were catatonic were drawn out of their catatonia to tap to the music," he recalled. "I said, 'Wow. Music has the power to bring people out of themselves.'"

"I never forgot that," he added. "That's what I've been doing ever since, really."

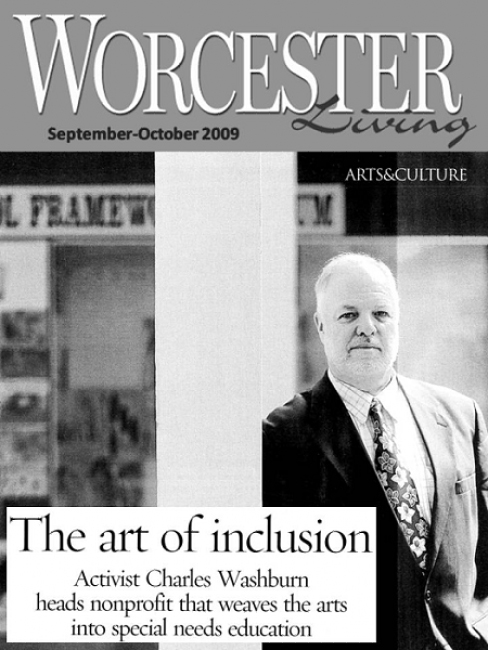

Washburn, 58, is executive director of VSA arts of Massachusetts. The small nonprofit is part of an international arts education network started by Jean Kennedy Smith in 1974.

These days, Washburn wears a necktie, manages a nearly $700,000 annual budget, and works on his sleek Apple laptop computer on commuter rail trains like a corporate executive. But he hasn't left behind the optimistic idealist who expected Worcester State Hospital to release a group of mental patients into his care for a rock concert.

Amid the worst recession in decades, with governments furiously hacking away at budgets like lumberjacks, Washburn has set himself the task of expanding VSA's reach into more schools and shifting its focus from training individual teachers to changing the way entire schools draw on arts.

"By using the arts, you create a new language that opens up a window onto the curriculum. It really engages all the senses," he said.

Although the Washburn name long has been a fixture in Worcester society, Washburn's branch of the family left in the early 1900s. He grew up in New Jersey and came to live in Worcester in 1972 for what he had expected to be a short stint while his wife, Frances Anthes, finished her degree in education at Assumption College.

Four decades, three children and one grandchild later, the couple still call Worcester home. Washburn initially worked as a kindergarten and primary school teacher at the former Worcester New School, an experimental parent cooperative then operating out of the old Friends Meeting House on Oxford Street. Washburn immersed himself in city politics and issues, especially in advocating for school funding.

From 1975 to 1984, he worked for Summer's World Center for the Arts, running the program by age 25. The center established a pottery studio and put on an annual summer art festival along with concerts, theater and dance performances.

A few years later, VSA approached Washburn to organize an arts festival in Worcester, mainly because he knew how to operate a commercial sound system - "a talent I picked up running anti-war demonstrations in college," he said.

VSA's founder in Massachusetts, Kennedy family friend Maida S. Abrams, hired Washburn as the agency's vice president and chief operating officer in 1987. He started commuting to Boston and took over as executive director from Ms. Abrams in 2000.

Washburn still lives in inner-city Worcester, in the same Crown Hill condominium on Congress Street where he and his wife raised their three children.

State Secretary of Education S. Paul Reville, another Worcester education advocate whose career led him to an executive job in Boston, describes the Washburns as people "in the best tradition of '60s action and idealism."

"They didn't depart from the ideals of social justice, peace and community. They haven't sold out or been co-opted by middle age or middle-class temptations," he said.

Washburn's first prolonged encounter with disability came in high school when he swept floors at an old schoolhouse used by United Cerebral Palsy of Union County, N.J. The job started out as nothing more than a means to put gas in his '59 Oldsmobile - a beloved car with soaring tail fins that would later throw a rod on his prom night.

His duties included meeting the buses of children arriving for after-school programs and then pushing their wheelchairs up sheets of plywood laid over the steps. He found that he enjoyed laughing and clowning with the children, many of whom were severely disabled.

"We had a grand time," he recalled. "It was then I learned not to be paternal or overly, well, not to pity people, and to see the wheelchairs as the tools of liberation that they really are."

Last spring, at Worcester's Elm Park Community School, in Kelle Lynch's class for students with behavioral problems, Washburn softly sang along from the back of the classroom as VSA artist-in-residence Tim Van Egmond strummed his acoustic guitar and patiently led the first- and second-graders in songs intended to entertain while teaching literacy and math skills.

Later in the class, three third-graders took turns reading a folk tale out loud to the class. Van Egmond, a professional musician, asked the class to quietly go through the motions of the actions described in the story, such as peeling potatoes and dumping a slop bucket, to focus their fidgety energy on the lesson.

Washburn noted that Van Egmond also stopped the story before the end to solicit ideas from the class about how the conflict in the tale could be resolved. The idea was to turn what could have been a passive experience into an intellectual challenge, he said.

"It's been a godsend for teachers and parents and the students themselves," Reville said of VSA's work. "There hasn't been a natural place for it in the overall structure of government, and Charlie has carved out a space for it and kept it going."

VSA works with some high schools, but Washburn acknowledged that it's more difficult to use arts to further inclusion of special needs children in the higher grades.

"It's hard to design a fully inclusive advanced placement calculus class. But it is possible to design a school where special needs kids are not in the basement," he said.

Washburn, ever the activist, started to grumble that one school in Worcester has fallen well short of that goal. But the outspoken former war protester quickly switched back into executive director mode. He declined to identify the school by name.

Over his decades in Worcester, Washburn has built a reputation as a fervent, but always amiable, activist.

"Charlie is low-key, but he's passionate," observed Worcester School Committee member John L. Foley, a fellow veteran of the school-funding battles of the early 1990s. "He believes in what he's doing, and he's persistent. He has his values and keeps putting those issues on the table."

In early April, VSA moved from its longtime headquarters in Chinatown to a renovated building on the edge of the financial district. The stark white walls and gleaming, honey-colored hardwood floors of VSA's new digs make it feel more like Newbury Street gallery space than a shoestring nonprofit. (The cost of the new lease is less than the old one, Washburn noted, because the space is much smaller.)

Washburn said the move is part of an overall strategy intended to raise the agency's profile and to extend its reach into more schools. That means raising more money. The artists-in-residence at 21 schools in Massachusetts, including in Worcester and Gardner, are the nonprofit's biggest expense by far at more than $350,000 a year.

In Washburn's assessment, VSA has been successful in furthering its goals at the level of individual teachers.

"But how do you change the whole school?" he said.

With state budget cuts and a persistent recession, it wouldn't seem an opportune time for a nonprofit to be contemplating an expansion.

About 65 percent of VSA's nearly $700,000 annual budget comes from grants and contributions, most of which are fairly stable because they are awarded on a three-year cycle, Washburn said. But fees paid by school districts that VSA works with account for roughly 20 percent of its budget.

Exhibiting the buoyant optimism he's known for, Washburn said he sees the financial crisis as a potential opportunity for the agency. Schools are under intense pressure to justify their spending with improvement in student achievement, he noted.

A cynic might argue that school administrators scrambling to cut expenses will be more inclined to wipe out fees paid to an outside agency than cutting their own staff and overhead. That remains to be seen.

But Washburn isn't a man given to defeatism. "In some ways," he mused, "the pressures schools are under are pushing them in our direction, because what we're doing is working."

TweetNo comments